About Paintings

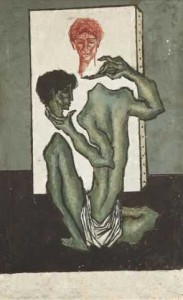

An exposure to Sadequain’s prodigious palette is a sight to behold. In a pure poetic Indo-Persian tradition, Sadequain employed powerful symbolism and metaphoric gestures in his paintings with abundance. He painted various series of paintings, each series rich with distinct creative idioms. Major body of his work can be categorized as Cactus Series, Mystic Figurations Series, Sun Series, Cobweb Series, Crow and Scarecrow Series, House of Cards Series, Sar-ba-Kuf Series, and Crucifixion Series, to name a few. His monumental murals exhibit sheer genius and his calligraphic work ushered in the renaissance of calligraphic art in Pakistan that cast him in a larger than life posture.

An exposure to Sadequain’s prodigious palette is a sight to behold. In a pure poetic Indo-Persian tradition, Sadequain employed powerful symbolism and metaphoric gestures in his paintings with abundance. He painted various series of paintings, each series rich with distinct creative idioms. Major body of his work can be categorized as Cactus Series, Mystic Figurations Series, Sun Series, Cobweb Series, Crow and Scarecrow Series, House of Cards Series, Sar-ba-Kuf Series, and Crucifixion Series, to name a few. His monumental murals exhibit sheer genius and his calligraphic work ushered in the renaissance of calligraphic art in Pakistan that cast him in a larger than life posture.

A bird’s eye view of Sadequain’s palette follows:

Portraits and Line Work

Sadequain was endowed with exquisite skill to execute impeccable line work and the ability to draw human figures and objects that make up the environment. In his early career during the 1950s, Sadequain painted realistic figures, still-life and portraits. But his realistic paintings detailed ordinary folks only. Contrary to the natural instincts, he avoided portraiture work in spite of invitations from the highest offices.

Cactus Series

Sadequain experimented with ideas, with his characters, with the surroundings, and the relationship between the object and subject. One of the objects that was the source of inspiration and influenced his work was the cactus plant. This plant survives starvation by the hostile waterless soil and scorching by the punishing heat of the sun, but the resilient plant thrusts through the rugged land, always pointing upwards, and bristling with life in spite of a hostile environment. Sadequain painted this imagery extensively during the decade of the 1960s.

He introduced powerful curves of the rippling muscles of sturdy workers in rough terrains into the cactus forms to show the power and energy of his characters. Sadequain said, “To me it symbolizes the triumph of life over environment.”

Mystic Figurations

In one variation of the cactus theme, he experimented with the hide-and-seek of light around the cactus plant. As the cactus branches reach up toward the light, the light beams pierce through the cactus branches and spread around the plant, casting an illusion of a delicate dance in celebration of life. In what he termed, Mystic Figurations, Sadequain made the light beams to form the impressions of existence with vigor and vogue. In this series of paintings, he captured the delicate relationship of light and dark by the judicious use of black, white, and crimson shades. He skillfully utilized the interaction of light and shadows in various shapes and forms and demonstrated how different forms would polarize, each complimenting and growing with the other, without disturbing the mystic effects between light and dark shades. Sadequain maintained that the shadows in these compositions were not merely a result of the physical phenomena, but they were an integral part of the composition.

Sun Series

In another variation of symbolic representation, Sadequain made effective use of the sun, as the provider of heat, light and energy in a series of paintings aptly titled the “Sun Series.” The prominent feature of these paintings is the treatment of light and dark shades, the contrast, which cannot be created without the light. Sadequain effectively painted the crimson hues of reflected sunrays from and through the maze of crisscrossing lines that sometimes looked like cactus branches and sometimes like landscapes. “It was the reflection of the rays of the crimson sun,” explained Sadequain, “which in mystic parlance defines darkness, as the darkness cannot exist without light in isolation.”

Cobweb Series

In another hallmark series of paintings titled the Cobweb Series, Sadequain depicted the cobwebs engulfing the society, including men, women, rich, poor, elite and the ordinary. According to Sadequain, the cobwebs become so ubiquitous they crowd the city streets, surround the buildings, cloud the thinking, and block the sight of the intellectuals and the ordinary. The charade becomes incredulous when people start using the cobwebs to decorate their abodes and even start engaging in the unholy act of worshiping them. In the end, mankind is rendered paralyzed by the cobwebs and the spirit of humanity is broken down.

The Crow and Scarecrow Series

The Crow Series reinforced the message of the Cobweb Series, by projecting men and women, who have been immobilized long enough that the crows start nesting, laying eggs and establishing their habitat over their heads. In a variation of this theme, Sadequain portrays the humans as gutless and obedient worshippers of scarecrows, which men themselves have erected to scare the crows but the crows are instead playing with them and even tearing the scarecrows to demonstrate to the spineless humans that they are mere hollow souls and cannot scare anyone. In an advanced stage of decadence, the society is headed to annihilation to be ruled by cobwebs, crows, lizards, and snakes; all symbols of doom.

House of Cards Series

The series titled “House of Cards” was painted in the summer of 1968. The faces of the characters on the playing cards bore expressions to match their assigned roles by the artist. Typically, a face was painted above and sometime repeated below, like a playing card pattern, and a spade or other card’s symbol was shown at one corner along with other symbolic patterns completing the painting. The king was portrayed as a tragic figure, his face looked haggard and he wore a crown of thorns. The queen was portrayed as a conniving and manipulative fox, plotting behind the back of the king. The knave was a cunning creature, who would plant the seeds of dissention between the king and the queen. In addition to these figurative compositions, Sadequain painted abstract forms in the playing cards style comprised of what can be termed as calligraphic strokes.

Sar-ba-Kaf Series

The poignant image of the decapitated head featured in a number of Sadequain’s paintings and drawings. The image is in memory of the martyrdom through decapitation of Sarmad Shaheed, Mansur-ul-Hajjaj (alternate al Hallaj) of Baghdad and of course the ultimate martyr, Imam Hussain, the grandson of the prophet Mohammad (PBUH). These victims of orthodoxy provided Sadequain with the powerful image of the headless man. The subject was close to Sadequain’s heart and it can be implied that the artist’s great fantasy was to follow in the tradition of the speaker of truth, who preferred to lay his life rather than deviate from the truth.

Crucifixion Series

The series of paintings titled “Crucifixion” depicts Christ on the cross, taking his last breath, but still barely alive to witness the crimes of the dark forces of society. The unscrupulous perpetrators, with no respect for the solemn occasion, could not control their appetite for crime even while the Messiah’s eyes were still open. In one dramatic composition, Sadequain showed the outcasts of society, even offering blood to the Christ in an act of defiance.

Hope I Series:

The “Hope I Series” represented his interpretation of the end of life, as we know it. One recurring feature of this series was a headless human figure, pinned to the ground amidst the decadence and corruption, but holding his severed head in his raised hand, affording an elevated and wider view of the sun of hope in the background and the hope lives on.

Hope II Series:

A follow up series of paintings titled Hope II presumably portrays a follow up stage after Hope I, a man lying on his back, with his knees raised enough for his legs to form an upside down letter “V” and holding his head in his raised palm. But his body has turned into a skeleton by now, signaling the end of the road, if something is not done soon. This series of paintings accentuate the ever-present pain of existence, while the facial expressions seem to convey a resignation to the facts of life.

In his characteristic style Sadequain fused human and beastly creatures in “Hybrid I and Hybrid II Series.” The compositions used mostly vertical and horizontal spear shaped strokes that adequately defined the contours of the characters. The colors he used for this series were mostly black and white applied in thick and straight lines.

Obsessed Series:

In quick succession Sadequain painted a series of paintings, the “Obsessed Series.” The prominent features of these paintings were oversized faces, which gazed at the on-lookers with intense, wide and bulging eyes. They appeared bewildered and possessive, perhaps a poignant hint at the prevailing state of affairs. Thick black lines and thick layers of paint in somber colors defined these paintings. Other variations in the composition portrayed wild and round eyes, bearing dark shadows, and glaring at far away distance rendered with strong line work, and colors are mostly black and white with stark contrasts, with few dabs of color of prominent strokes.

Poetic Interpretations of Ghalib, Iqbal, and Faiz

Sadequain was a painter-poet, whose creative pursuits, both in the realm of arts and poetry, found their expressions from the same source. His paintings read like his poetry and his poetry conjures images of his paintings. He expressed the singularity of his inspiration in one of his quatrain:

Ek bar mein sahiri bhi karkey dekhoon

Kia farq hai shaeeri bhi karkey dekhoon

Tasveeron mein ash-aar kahey hein mein nay

Sheron mein musawwiri bhi karkey dekhoon

Once I would want to serenade for pleasure

To experience the difference, I would now compose poetry

My paintings recite the poems that flow within them

Now I compose poetry to compliment my painting

Searching for new expressions, Sadequain gravitated to illustrate the most complex concepts expressed in the poetry of the stalwarts of Urdu language, Ghalib, Iqbal and Faiz. A tall order for the ordinary and mundane, but it was natural for him to engage in one of the most significant bodies of his work. He did not complete the marathon of illustrating the select poetry of Ghalib, Iqbal and Faiz in one stretch, but he delved into the intellectual discourse at regular intervals when he heard his calling.